|

Home | Photos |Facebook| Taps

HonorRoll | Base Camp | Reunions

Absent Comrades | Contributor's Corner

Maj. Gen. George S. Patton, Dead At 80

By Matt Schudel

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, July 1, 2004; Page B06

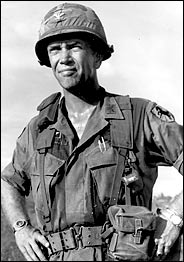

Patton Family ArchivesGen. George S. Patton; Son of Famed WWII Leader

George S. Patton, who was the son of the famous World War II general and who became a major general in the Army himself, died June 27 at his home in Hamilton, Mass., at age 80. He had a degenerative form of dementia.

Funeral services were held at St. John's Episcopal Church, Beverly Farms, MA on Wednesday, July 7 at 10:00 a.m.He was a cadet at the U.S. Military Academy during World War II, when his father, Gen. George S. Patton Jr., rose to prominence as one of the most beloved and feared Allied military leaders.

The younger Gen. Patton graduated from West Point in 1946 and spent 34 years in the Army. After his father's death in an automobile accident in 1945, he legally changed his name from George Patton IV to George Smith Patton. (There was no George Patton III.)

He was a company commander in the Korean War and was a colonel during three tours in Vietnam, where he commanded the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, called the Blackhorse Regiment. Much like his father, whose nickname was "Old Blood and Guts," the younger Gen. Patton received both plaudits and opprobrium for the zeal his forces demonstrated in battle.

"Find the bastards and pile on" was his unit's motto in Vietnam.

"I do like to see the arms and legs fly," he once told his soldiers.

At his farewell party when he left Vietnam, then-Col. Patton brandished a skull with a bullet hole through the forehead, according to an article in the New York Times Magazine.

Over the years, Gen. Patton was often asked about his father, and he chose a career in which comparisons were inevitable.

"He didn't dwell on it," said his wife, Joanne Holbrook Patton. "It was a fact of life. He usually said, 'Yes, of course there is a responsibility, but it's also a privilege.' He said he couldn't dwell on it because he was too busy with his own career."

Gen. Patton received a master's degree in international affairs from George Washington University, graduated from the Army's War College and did graduate study in management at Harvard. After Vietnam, he commanded the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Hood, Tex. -- the same unit his father had led in North Africa during World War II. He retired from the Army as a two-star general in 1980, having twice received the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army's second-highest award for combat valor, the Distinguished Service Medal and the Purple Heart.

After his retirement, Gen. Patton settled on a 250-acre farm in rural Massachusetts. He began by raising blueberries, and more than 200 varieties of produce are now grown on the farm. He named the fields on his farm in honor of soldiers killed in combat under his command.

In 1984, he called Sen. John F. Kerry (D-Mass.) "soft on communism" for his antiwar stance during the Vietnam War and charged that Kerry "gave aid and comfort to the enemy and probably caused some of my guys to get killed." Those statements have been resurrected by conservative commentators during the current presidential campaign.

"My husband was outgoing and outspoken," his wife said. "I would not presume to speak for him today, but you must remember his troops and their welfare were the most important things to him."

Gen. Patton was posted to bases near Washington three times and, at the time of his retirement from the Army, lived in Bethesda. He and his wife were married in 1952 at Washington National Cathedral. None of their five children entered the military.

Besides his wife, of Hamilton, survivors include five children, Margaret Georgina Patton of Bethlehem, Conn., George S. Patton Jr. of Hamilton, Robert H. Patton of Darien, Conn., Helen Patton-Plusczyk of Saarbrucken, Germany, and Benjamin Wilson Patton of New York; six grandchildren; and a great-grandson.

© 2004 The Washington Post Company

_________

I attended the funeral. Read my account here.

Hamilton / Wenham Chronicle General Patton's Hometown Newspaper (Reprint)

Photos Of Gen. Patton's Internment - Arlington National Cemetery by John Van Nus.

Other Links To This Story

Washington Post

KWTX

WoodTV

For More on the death of General Patton Go To The 11th ACVVC website.

Home | Base Camp | Photos |

Guest Book | Taps | Contributor's Corner

Honor Roll | Links | Feed Back | Reunions | Search | Site Map